The BBC recently put out an audio drama adaptation of C.S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength. This is one of my favorite books, so I was naturally excited about the prospects here. I wanted this to succeed. With that being said, I certainly had a degree of skepticism, as the profoundly anti-modern philosophy of Lewis’s dystopian fairytale is hardly what I would associate with a major media institution such as the British Broadcasting Corporation. After all, England unironically has its own N.I.C.E. (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). It turns out that my skeptical impulses were correct: the celestial wisdom of Lewis was lost to the forces of this silent planet.

[In case it needs to be said, I will be discussing major spoilers regarding the book as well as BBC’s adaptation.]

To be fair, it is impossible for anyone to condense a tome like That Hideous Strength into a two hour adaptation without cutting out a considerable amount. This could raise the question as to whether it should have been condensed to two hours, but I’ll accept this limitation for the time being. With that in mind, the pacing is decent, even if it misses some of the meandering feel that is quite significant for the story. Also, I enjoyed the music transitions. Beyond that, there is not much left for me to praise.

First, let us consider what That Hideous Strength is so we can evaluate what it is for and where exactly the adaptation misses the Mark (pun intended). In his prologue to That Hideous Strength, Lewis explicitly states that this is a fairy tale primarily meant to illustrate his arguments in The Abolition of Man. In other words, this is not a story that happens to have some points for philosophical reflection. This is a philosophical story that, apart from that philosophy, is not that story. Furthermore, this novel is inseparable from the dialectic established by the previous two books. It is sometimes said that That Hideous Strength can be read in isolation, but I strongly disagree. Sure, the basic plot can be followed, but the essence of the story is tied to the broader metanarrative, which frames this story as a philosophical and archetypal tale. In what follows, I will discuss a few major ways that the adaptation utterly hollows out the story.

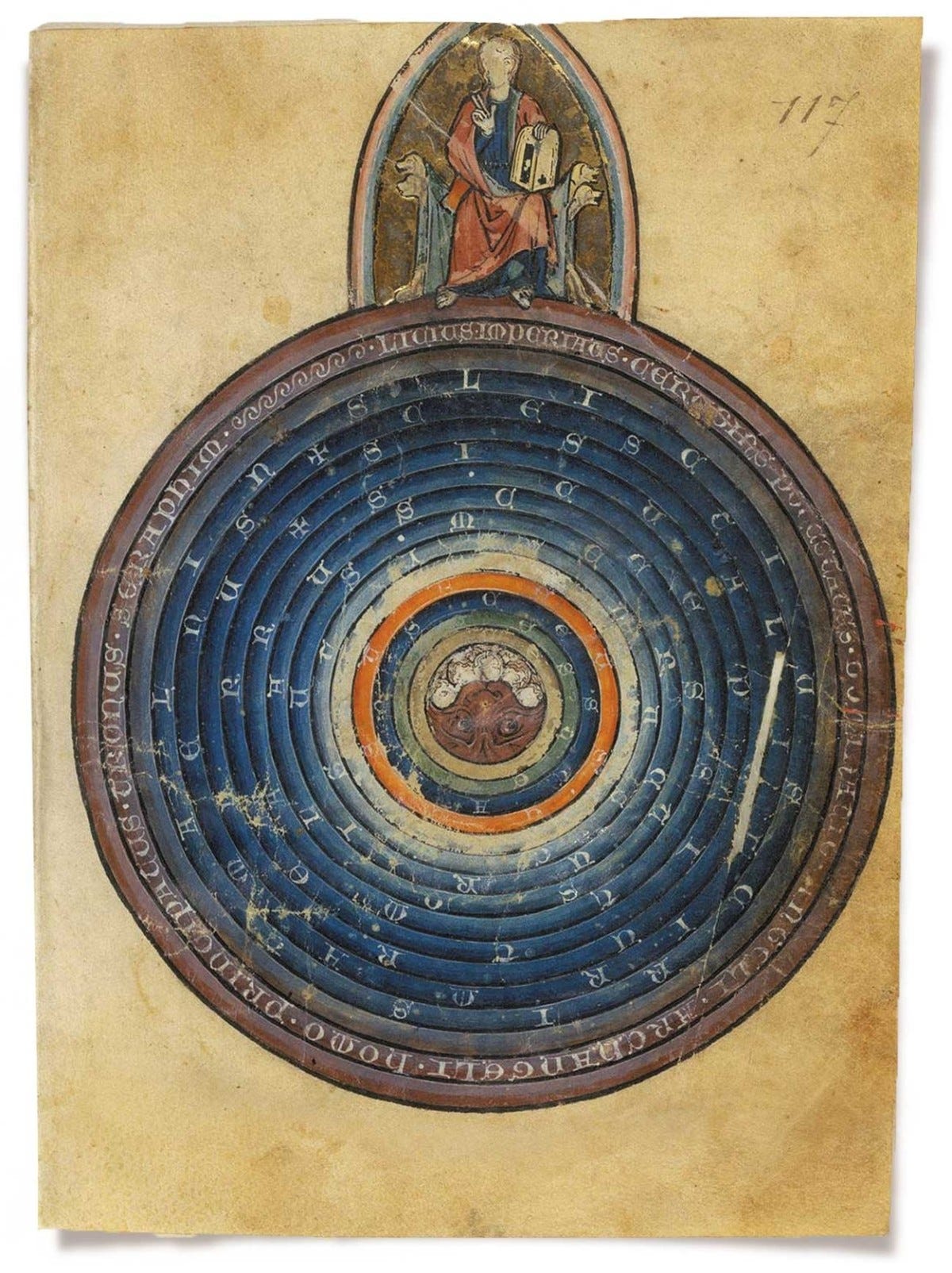

In Out of the Silent Planet, Elwin Ransom becomes associated with the masculine, martial influence of Mars. In Perelandra, Ransom is a martial agent brought into relation with the feminine, life-giving influence of Venus. In That Hideous Strength, which takes place on the isolated, disordered planet Earth, the story begins with the word “matrimony,” thereby giving us the masculine-feminine relationship established between the previous two books. However, the particular marriage in view is cold and disordered because, again, this is a story of Earth rather than the heavens. In the book, Mark and Jane Studdock are essentially estranged, but, through their individual stories, they become reconciled as they become rightly aligned with their heavenly ideals in conjunction with the jovial influence manifested in Ransom. (I tried removing the passive voice of that sentence, but it is actually important here.) Almost any hint of this fundamental aspect of the story is simply missing.

Amidst the discordant relationship between Mark and Jane, the book quickly brings us to Mark’s academic context. It is particularly important to note that Mark is a sociologist. If this is mentioned in the adaptation, it is brief, passing, and unremarkable. In the book, however, it is mentioned on many occasions to drive in the point. For Lewis, “sociologist” is generally a pejorative term. In particular, he is opposed to sociological philosophy, which is connected to his broader critique of democracy-as-philosophy. Lewis defends democracy as a pragmatic good for restraining tyranny, but he believes it is demonic if taken as an accurate representation of what reality is actually like. Reality is hierarchical. Some things are better than other things. Some people live better lives than others. Most significantly, ideals stand above particulars. Sociologists, however, tend to think democratically: “Here is what people believe/how people act; therefore, here is what we should view as normal.” This is the same problem he has with evolutionary philosophy: “Here is what is happening; therefore, here is what should be happening.” Thus, when Lewis emphasizes that Mark is a sociologist, he is telling us something significant about his character arc. Furthermore, Mark the sociologist is obsessed with getting into the inner circle of the “progressive element” of his college. If you have any experience with academia, you know what this circle is. As you get further into the story, you really come to understand what this circle is. Riffing off of Dante, this progressive element of modern academia is the outer circle of Hell that spirals down into the National Institute for Coordinated Experiments, which is led by likes of “Frost” and “Wither,” names that remind us of Dante’s frozen inner circle. Thus, Lewis is making a very polemical point here regarding the places of power in modern academia. This entire element of the story is utterly absent from the audio adaptation. There is not one mention of the “progressive element,” and it is not difficult to figure out why this is the case. (For more on Lewis’s critiques of democracy-as-philosophy, you can read his essay “Equality” or “Screwtape Proposes a Toast.”)

Next, let’s talk about Ransom. In the book, Ransom the Pendragon is this overwhelming figure who represents the priest-king Jupiter, whose influence governs the relation between Mars and Venus. When Jane first encounters Ransom, she is unmade in his presence and, as she leaves that meeting, she is enraptured in his heavenly influence and becomes awakened to the celestial beauty in which she might participate. By the end of the story, she fully embraces this beauty as she rejects the terrestrial influence of sin in favor of the redemptive grace of God. In the BBC’s version, however, Ransom is a rather underwhelming man who laments his crippling weakness and occasionally and awkwardly offers to pray for Jane, who remains unconverted. This is not just a matter of leaving a few things out for the sake of time. This is an absolute subversion of Ransom’s character and the Christianity that makes him such a profound figure.

Now, let’s briefly discuss the main players at the N.I.C.E. First, there’s the deputy director John Wither. Lewis describes Wither as having an eerily amicable, somewhat senile, hauntingly otherworldly presence. As the story progresses, he is revealed to be downright demonic, to the point that it is not clear if there is still much “John Wither” present at all. In BBC’s version, all hints of the demonic are removed. He is just an ordinary guy who happens to be a smooth-talking leader of a bad organization. Next, there’s Fairy Hardcastle. In the book, her primary character is one of un-feminized, disordered sexuality, providing us with another manifestation of the N.I.C.E.’s rejection of “the normal.” Unsurprisingly, the BBC was unwilling to enter into this territory, and she too was just an ordinary woman who happened to work with some bad people. Lastly, let’s consider Professor Augustus Frost, the materialist psychiatrist who understands everything in those terms. Of all the N.I.C.E. leaders, he likely received the best treatment in the adaptation, although even he was considerably weakened. For example, at the end of his story in the book, he is frozen by his lack of agency that is the inevitably result of his materialism, which in turn is a demonic deceit. Something like this happens in the adaptation, but Lewis’s philosophical critique is entirely missing. Aside from a couple passing statements made by Ransom, the diabolical nature of the N.I.C.E. philosophy is entirely obscured, thereby providing us with an unremarkable group of villainous mad scientists.

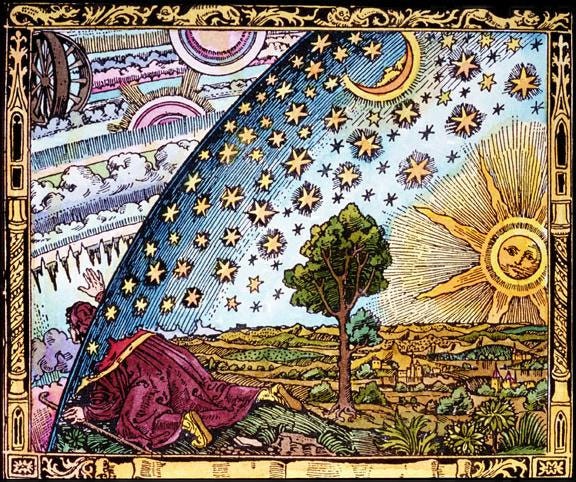

Finally, let’s talk about the finale. In the book, the company at St. Anne’s is regularly confused about what exactly they are meant to be doing. For the most part, they are okay with that, because they trust Ransom who in turn trusts God and his heavenly court. The one who has the greatest struggle with this arrangement is Andrew MacPhee, who is entirely absent from the BBC’s adaptation. As we approach the end of the story, it becomes increasingly clear that they are not really meant to do anything apart from remaining faithful. As with Babel of old, it is Heaven that will smash the pride of man. Thus, the forces of heaven descend upon Merlin with an act that will be his undoing and his redemption. Operating through Merlin, the heavenly Powers bring the curse of Babel upon Belbury and the N.I.C.E. implodes in its confusion, which is both a curse and a consequence of their stance against the Real. In BBC’s version, there is no descent of Heaven. Jane, in scorn of her Venusian ideal, takes charge and hops in a car with Merlin to save Mark while pitiful Ransom laments not having the strength to go with them. Then Merlin, apparently with his own magic, jedi mind tricks the guards and curses Belbury with confusion. They then rescue Mark, who never becomes a martial figure, and the story ends.

Lewis’s story is one of romantic idealism and philosophical critique of the modern tendencies in academia and science to forsake the Real, the Ideal, and the Normal in favor of evolutionary “whatever comes next is good” philosophy. BBC missed this entirely or, more likely, they excised it because it would be impossible to include it without the recognition that they are far more aligned with Belbury than they are with St. Anne’s.

About the Author

Andrew Snyder holds a Ph.D. in theology with a dissertation on Søren Kierkegaard’s theology of self-formation. He is a professor of philosophy and religion, the host of the Mythic Mind podcast, and the founder of the Mythic Mind Fellowship. You can follow him on Twitter @andrewnsnyder and find his often-neglected personal Substack on The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien at Andrew N. Snyder.

Join the Mythic Mind Fellowship and/or enroll in a course at https://www.patreon.com/mythicmind

I’m surprised they were brazen enough to try. Perhaps they failed to understand the material and didn’t know they were vampires playing with holy water ….

Of course the “media experts” (BBC) would be the ones to adapt a book where the experts (N.I.C.E.) are the baddies :)

That Hideous Strength is a masterclass in what happens when one embraces materialism. I have a few interviews on my substack podcast with Joseph Weigel where we tackle some aspects of this amazing book.