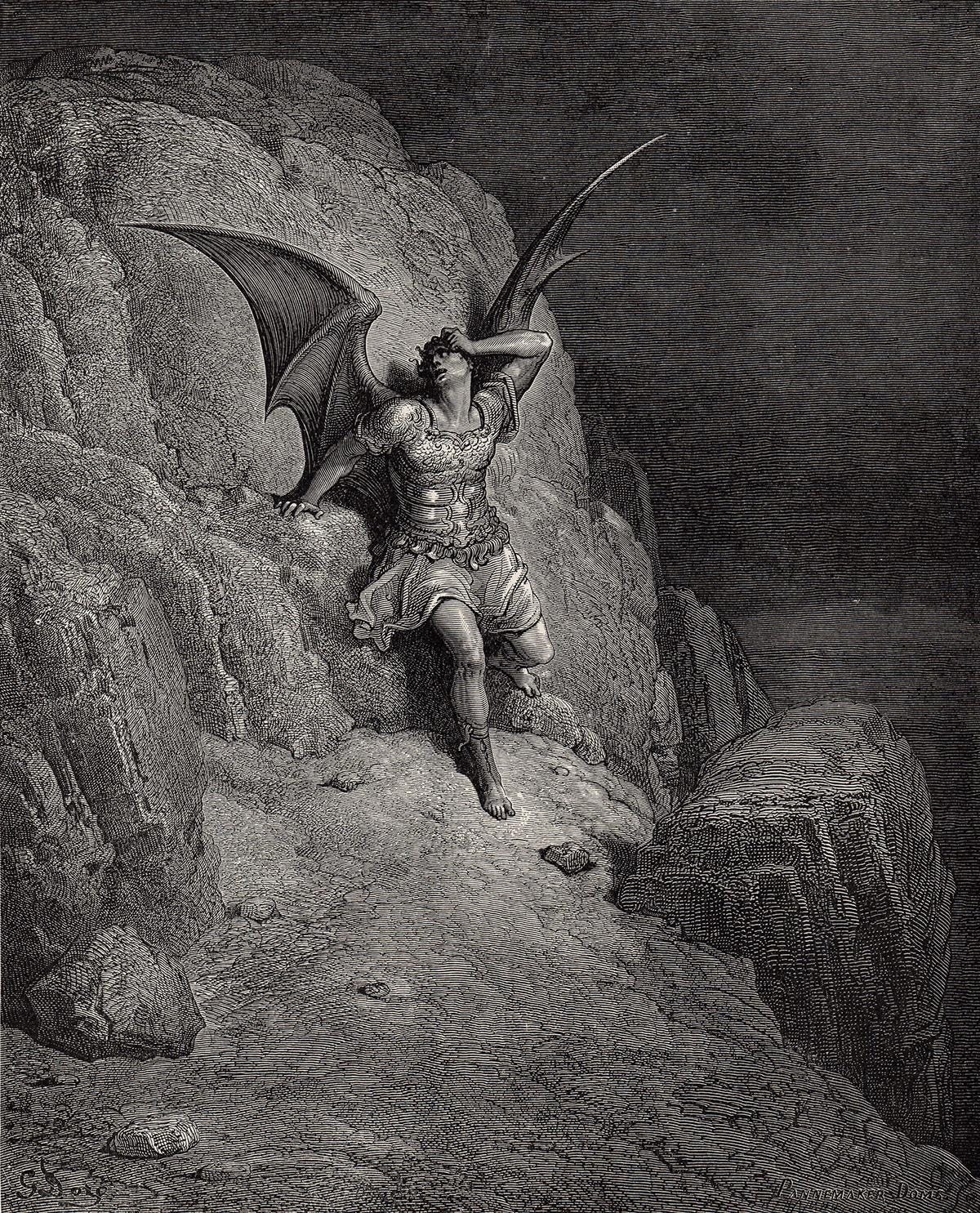

After the opening preamble of Paradise Lost, there is a natural flow from a description of the fall to a narrowing focus on the cause itself, Satan, who is the speaker in the first dialogue scene of Milton’s great poem (84). Book 1 describes Satan’s temporal and spiritual condition after being cast out of heaven with the demons that followed him, but I want to focus on how Satan takes command as the hellacious leader of a legion of numberless fallen angels (344). Because for Milton, Satan represents the tyrant of hell just as God represents the monarch of heaven and all created order.

But if Satan is the authoritarian ruler of hell, then why is he given such a presence in the narrative? The choice of Milton to give Satan a major role in the drama and dialogue throughout Paradise Lost has been the subject of much scholarly debate over the years.1 For context, I will briefly mention that I side with the view C.S. Lewis takes in A Preface to Paradise Lost, which essentially states that Milton made Satan a major character in the epic because he is supposed to be someone that we can relate to and identify with.2 As Lewis states: “it is a very old critical discovery that the imitation in art of unpleasing objects may be a pleasing imitation.”3 For this reason, Milton unashamedly puts Satan’s charisma and charm on full display, conveying in Satan “the glamour, even the majesty of evil, without diminishing, so to speak, the evil of evil.”4 This naturally makes us modern readers uncomfortable, especially in an age where people have a tendency to be overly sympathetic to villains; yet Milton’s Satan is not one who is meant to be sympathized with, but rather he serves as an image just as the shades in Dante’s Inferno, whom reading about is like gazing into a mirror in which we are to see and reflect upon our own sin as we meditate on the imagery in the poetic narrative. In Paradise Lost, Satan isn’t uncomfortable to us because Milton chose to portray the king of hell as charismatic, charming, and witty; he is uncomfortable to us because he reveals to us the worst in ourselves: that we have also fallen and have sinned against God. Like Satan, we live with monomaniacal concern with the self and our supposed rights and wrongs as a necessity of the Satanic predicament.5 In essence, we are all tyrants in our own way, especially in how we relate to God.

As for the tyrannical role of Satan, a major aspect of this is his sophist rhetoric, which works in concord with his role as “dread commander” (589).6 Satan’s speech in book 1 calls the demons, who appear to be defeated, to rise and get back to work (186–91). Rallying the crowd of vanquished demons that lie before him, there is a sense in which Satan embodies some of the worst of modern scientism, where he sees the fall as a first experiment that failed, but that with progress and an elevation reason, they can find a solution to muddle God’s plan: “The mind is its own place and in itself can make a Heav’n of hell, a Hell of Heaven” (254–5). This kind of proto-Nietzschean imagery7 certainly led the 19th-century criticism, such as the opinions of Blake, that Milton was “of the Devil’s party without knowing it”,8 but Milton was no fanatic of Satan, rather, he is trying to teach us many things about fallen beings in general.

One specific dimension of this is that Satan is the ultimate archetype of the danger in following a charismatic leader. As humans, many of us are made to be followers rather than leaders, but in a pre-fallen world, we don’t have the breakdown of following the wrong leaders, for God sits rightly at the top of the hierarchy of creation as the uncaused cause of all; and worship, rightly so, is fully rendered as it is deservedly due to him. But as for Satan, we see the first perversion of leadership gone wrong. During one of his speeches, Satan commands the demons: “Awake! Arise, or be for ever fallen!” (330). Though Satan likely knows he cannot defeat God, he does believe that he can craft a way to get back at God. Therefore, he brings out his lofty speechcraft, assuring them to rise up and offend God as much as possible, rather than accepting their defeat. However one interprets Satan’s view of his relationship to defeating the heavens in this scene, it is apparent that Satan does possess the power of the most dangerous charismatic cult leader of all time, because Milton immediately describes the demons’ responses to Satan as their leader, and this highly detailed and descriptive response goes on at length (331–621). Beyond a drawn-out description of almost 300 lines in the middle of book 1, Satan speaks at the end of book 1, eliciting another descriptive narrative from the demons (663–798) which carries us all the way to the infernal court of Pandemonium (792), the high capital of Satan and his peers (756–7), which is the setting of book 2.9

The demons do not speak in their response, but rather Milton illustrates for us the power which Satan has over them. His leadership is not just of a great general, but that of the most horrific cult of personality of all time. Satan has a commanding presence, and his talons dug deep into the will of the demons, a power that leaders such as Julius Caesar, Vlad the Impaler, and Hitler could have only dreamed of harnessing and possessing for their self-justified ends. There are many lines in book 1 that capture this vividly, but I have selected two brief passages to illustrate this point:

“They heard and were abashed and up they sprung

Upon the wing, as when men wont to watch

On duty, sleeping found by whom they dread,

Rouse and bestir themselves ere well awake.

Nor did they not perceive the evil plight

In which they were or the fierce pains not feel,

Yet to their general’s voice they soon obeyed

Innumerable” (331–8).10

This first passage takes place after Satan’s initial exhortation to the demons, after he has completed his dialogue with Beelzebub. In context, this passage shows us the power of the tyrant to take rightfully defeated beings and turn them into minions for his cause. It only takes Satan several crafty lines of dialogues to completely change the disposition and motivation of the fallen angels, getting them back on board with his ideology which got them all in this mess to begin with: that it is “Better to reign in Hell than to serve in Heaven” (263). With cunning wit and manipulation, Satan has led the demons to buy into his narrative, making the sharp accusation that God “Sole reigning holds the tyranny of Heav’n (124). Satan has projected himself onto God, and the demons, in their broken state, accept and rally behind. Where the passage above shows Satan’s initial rallying of the troops, the passage below serves to illustrate this further:

He spake, and to confirm his words out flew

Millions of flaming swords drawn from the thighs

Of mighty cherubim. The sudden blaze

Far round illumined Hell. Highly they raged

Against the high’st and fierce with grasped arms

Clashed on their sounding shielfs the din of war,

Hurling defiance towards the vault of heaven” (663–9).11

The second passage selected describes the response of the demons as they prepare to take counsel in Pandemonium. After they raised ten thousand banners and a forest of spears into the air (545–7), symbolizing their now unified purpose under the command of Satan (559–62), they respond to the command of their mighty chief in full rebellion, ready to plot and attempt to ruin whatever providential plans God has in store for creation. Here we see something that is alarming and unfortunately true in world history time and time again: that a tyrant who knows how to manipulate others to his ends is a force to be reckoned with. This is the type of person in the world who can do more damage with their speech craft than most people could do with anything physical, and Satan embodies the most extreme form of this, for he is not just an earthly instantiation of evil, but rather is the supernatural, cosmic symbol of evil itself. Satan is the originator of pride, rebellion, and evil itself as he led the fall of angels before Eve would ever partake of the “fruit of that forbidden tree whose mortal taste brought death into the world and all our woe with loss of Eden” (3– 4).

Though Satan is the tyrant over hell and possesses supernatural power that we do not have the capacity of being for, we still are tyrants in our own right. Because for Milton, Satan is disturbingly relatable to us: for heaven understands Hell, but Hell does not understand Heaven, “and all of us, in our measure, share the Satanic, or at least the Napoleonic blindness. To project ourselves into a wicked character, we have only to stop doing something, and something that we are already tired of doing; to project ourselves into a good one we have to do what we cannot and become what we are not.”12

Overall, we see that Milton’s Satan is nothing like Dante’s Satan, who is half-frozen at the bottom of hell, completely static in his misery,13 but rather this Satan is alive with a charismatic presence in which he can make quick work of summoning the full legion of fallen angels to his command and will, exerting them to take on a sort of will to power after their defeat, rather than wallowing in their own misery and eternal defeat, such as Dante’s Satan does. We should not simply dismiss our connection to Satan and project that into Milton but rather understand that Milton is putting Satan directly in front of us as a reflection to know what we are as members of Adam’s rebellion. But also to know that we don’t have to continue in Satan’s path forever, rather we can be redeemed by the one greater man who will restore us and regain the blissful seat (4–5).

1 Stanley Fish, Surprised by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost, 2nd Edition, (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 2003). Fish identifies the two camps as one proclaiming that Milton was of the devil’s party with or without knowing it (Blake and Shelley), the other proclaiming that the poet’s sympathies are obviously with God and the angels loyal to him (Addison and C.S. Lewis). In this work, Fish’s thesis is to reconcile these two camps into one.

2 C.S. Lewis, A Preface to Paradise Lost, (HarperOne: New York, 2022), VI. C.S. Lewis credits his friend, the great 20th-century literary scholar, Charles Williams, for recovering the “true critical tradition after more than a hundred years of laborious misunderstanding.” This is a direct criticism of and declaration of opposition to the Blake and Shelley camp of Milton interpretation in the 19th-century.

3 Lewis, 117.

4 Gordon Teskey, “Introduction,” in Paradise Lost, edited by Gordon Teskey (W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2020), xxviii

5 Lewis, Preface to Paradise Lost, 127.

6 The following epithets are also used to describe Satan in book 1: great admiral (294), general (337), great sultan (348), great emperor (378), mighty chief (566), and dread commander (589).

7 Satan essentially asserts a kind of Will to Power throughout books 1 and 2 of Paradise Lost, as he commands his demons to abandon the objective morality of the Chrisitan framework and to rise and create their own meaning through the assertion of power in creation.

8 William Blake, “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793),” in Paradise Lost, edited by Gordon Teskey, (W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2020), 412.

9 I cannot recommend Chapter 14 of A Preface to Paradise Lost enough for insight into Moloch, Belial, and Mammon and how their responses reflect a further downward spiral into the Satanic Predicament.

10 Milton, Paradise Lost, 14.

11 Milton, Paradise Lost, 24.

12 Lewis, Preface to Paradise Lost, 126.

13 See Inferno Canto XXXIV, lines 28–69 for a vivid description of Dante’s Satan.

Join the Mythic Mind Fellowship here: patreon.com/mythicmind

Enroll in Josh’s Introduction to Paradise Lost class here: patreon.com/joshtraylor

As a reminder, Mythic Mind patrons get a 50% discount on courses led by Fellowship creators!

Mythiché