The Ancient Origins of the Nibelungenlied

The greatest medieval German epic contains echoes of the past and future

Human beings love myths. They undergird the narratives by which we live our lives, or as the philosopher Charles Taylor would say, our “social imaginaries.” Throughout history, as humans have wrestled with questions of national, ethnic, religious, and imperial identity, myths have served to enhance and focus their longings.

As my husband and I prepared to visit Germany this past summer, I decided to fulfill a longtime goal and read the Nibelungenlied, also known as The Lay of the Nibelungs. Written in the old German language during the high medieval period (12th century), this epic tale of heroes and revenge took on new significance in the 19th century during the push for German statehood, when the discovery of old manuscripts led to its identification as the national myth of the German people. Richard Wagner took inspiration from it for his famed cycle of operas, The Ring. Fritz Lang produced a pair of films that were a hit in Germany during the Weimar Republic period. Then those chief opportunists, the Nazis, who could never resist anything that seemed sort of old and Germanic, drew on the Nibelungenlied for propaganda purposes.

Long before the history of both Germany and the Nibelungenlied grew dark, this tale of buried treasure, superhuman strength, and women scorned held immense value as a cultural artifact. It is particularly useful for understanding the reception of history and oral tradition, as the Nibelungenlied contains echoes of real people and events alongside its more fantastical elements. It draws upon the earlier myths of the North Germanic and Scandinavian peoples, along with the history of the Western Roman Empire’s collapse.

Perhaps most fascinating is the way that one can see Northern Europe’s religious transition within the text of the Nibelungenlied. The areas of Europe that lay beyond the bounds of the Roman Empire—such as northeastern Germany and the Scandinavian lands—were among the last to convert to Christianity en masse. The Baltic Sea was a mostly pagan waterway up to the time that the Nibelungenlied was written, generally holding to the old pantheon of deities: Odin, Freyja, Thor, Loki, Frigg, etc. To the extent that the Nibelungenlied is influenced by the mythology of Northern Europe, it bears these pagan traces.

But the author of the Nibelungenlied seems to have resided in what is now southern Germany, and much of the action takes place in the valleys of the Rhine and Danube Rivers. These are territories where the Romans held sway and Christianity was introduced much earlier. Whoever wrote the Nibelungenlied was clearly influenced by the traditions of courtly behavior that had come to dominate the French-speaking lands and seeped into neighboring kingdoms like the German-dominated Holy Roman Empire. So, amid the old pagan themes, we find in the Nibelungenlied a tale that is absolutely obsessed with courtly traditions and niceties.

My goal in this series of essays will be to assess the more pagan side of the Nibelungenlied through comparisons with other works. First, there are sagas that were written before the Nibelungenlied or represent an earlier, more pagan way of thinking: the Poetic Edda (written in Iceland) and the Volsunga Saga (written in Norway). Second, there are works that have come after the Nibelungenlied and been inspired by it. Here the examples I will consider come from the legendarium of J.R.R. Tolkien, particularly The Silmarillion. As I examine the connections between these works, I will focus on three themes that are largely pagan in nature: 1) Doom, 2) Bloodshed, and 3) Heroism.

Summary of the Nibelungenlied

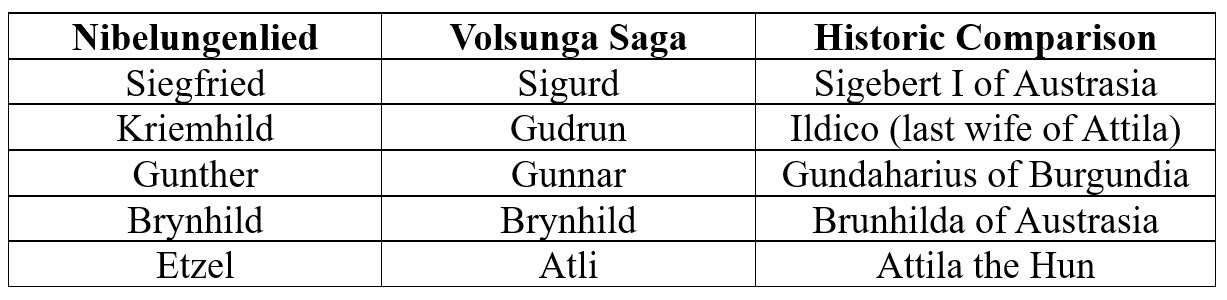

Before I launch into an examination of the Nibelungenlied’s themes, it will be helpful for me to provide an introduction to the story for those who have not read the work. (Though I would highly recommend that you dive into it yourself at some point!) The story centers around six characters: Siegfried, Kriemhild, Gunther, Brynhild, Hagen, and Etzel. Of these six, five also appear in the Volsunga Saga and Poetic Edda, and those five have all been linked in some manner to historic figures around the time of the Migration Period in Europe (4th through 6th centuries A.D./C.E.) and the accompanying Hunnic invasions of the Roman Empire. The chart below links the five Nibelungenlied characters with their Scandinavian equivalent and the historic figures that most likely inspired them.

As you can see, the Roman provinces of Burgundia and Austrasia (which later gave their names to the kingdom/duchy of Burgundy and the nation of Austria) are at the center of the historic tale. These lands corresponded roughly to the upper and middle Rhine Valley (western Germany), as well as parts of eastern France and Switzerland. Under their most famous leader, Attila, the armies of the Hunnic tribal federation marched directly through this area in 451 A.D./C.E. on their way into Gaul. The complicated politics of the period were preserved as folk memories among the many peoples who were migrating. They took fractured bits of information with them into what is now northern Germany and the Scandinavian countries. Thus, the related sagas were born.

Siegfried is the greatest hero of the Nibelungenlied. He is a prince of the Netherlands who rides to the Burgundian capital city of Worms in pursuit of the hand of the fair princess Kriemhild. This seems standard enough, but there is also a brief section in which a more fantastical backstory is related: Siegried won the vast treasure of the Nibelungs, including an invisibility cloak, and he slew the dragon Fafnir and bathed in its blood, making his skin hard and invulnerable to weapons.

Kriemhild is a princess of Burgundy, sister of the king, Gunther. She is described as the most beautiful maiden in the world. However, Kriemhild has had a dream which she interprets as a prophecy that her husband will be violently killed. She is therefore determined never to marry.

Gunther is the king of the Burgundians, a man of upstanding character, but less acclaimed in battle than Siegfried. When the Netherlandish prince arrives, Gunther forms an alliance with him, and together they confront Gunther’s enemies to the north. Siegfried enters into a deal by which he will win the right to marry Kriemhild. (More on that in the next section.) When Siegfried meets with success, Gunther grants him the hand of Kriemhild, who despite her earlier protestations against marriage, has fallen deeply in love with Siegfried and happily consents to the match.

Brynhild is the queen of Island (thought to be a perversion of Iceland) renowned for her superhuman strength. She has pledged that she will only marry a man who can defeat her in an athletic contest, and failed applicants will be put to death. So far, the result has been a lot of corpses and no wedding. Gunther wishes to wed Brynhild, but he knows he can never best her in a show of strength, so he makes a deal with Siegfried: he will grant Siegfried the hand of Kriemhild if Siegfried assists Gunther in winning Brynhild. Siegfried’s strategy is to hide under his invisibility cloak and secretly help Gunther during the challenges. They meet with success, with Brynhild none the wiser. Gunther and Brynhild are married, as are Siegfried and Kriemhild.

Hagen is a high-ranking noble at the Burgundian court. He develops a dislike for Siegfried, perhaps because the foreigner has become the king’s favorite rather than Hagen. But the real turning point comes due to the marriages. Despite her earlier pledge, Brynhild refuses to sleep with her new husband Gunther. When the hapless king attempts to overpower her, Brynhild simply ties him up and hangs him from the ceiling. The following night, Gunther enlists Siegfried to put on his invisibility cloak and overpower Brynhild. This Siegfried does, and because it is dark, Brynhild does not catch on to the plot. When Gunther slips in to do the deed, Brynhild responds passively.

What Gunther does not know is that contrary to his firm pledge, Siegfried actually slept with Brynhild himself before Gunther entered the bed chamber. Brynhild has no idea that it was Siegfried who overpowered her twice, nor does she realize that Siegfried is a great ruler in his own right: she thinks he is merely Gunther’s vassal. Some time later, Kriemhild and Brynhild get into a dispute over who is higher ranking. When Kriemhild finally reveals that Siegfried is king of the Netherlands (his father having passed), and it was he who not only won Brynhild’s hand, but also took her virginity, Brynhild is humiliated and enraged. Hagen is offended and alarmed by what he perceives to be Siegfried’s violation of the code of honor. So, Hagen convinces Gunther that they should kill Siegfried. During a hunting trip in the woods, Hagen and his companions are able to spear Siegfried to death after Kriemhild is tricked into revealing that there is one spot on Siegfried’s back that was never touched by the dragon’s blood.

Etzel enters the story in the second half, after Siegfried has been murdered and Kriemhild has set her mind on revenge, for she knows Hagen and Gunther to be the authors of the killing. Kriemhild agrees to a new marriage with Etzel, king of Hungary. (The Huns do not actually seem to have been the ancestors of the present-day Hungarians, but many medieval Hungarians would have believed as much.) After some time passes, Kriemhild invites the entire Burgundian court to visit the Hungarian court. Gunther and Hagen both suspect treachery, but the code of honor requires them to attend. Once at the Hungarian court, the Burgundians end up in a conflagration of escalating violence that ends with the deaths of nearly everyone involved, with Gunther, Hagen, and Kriemhild being the last to fall. Kriemhild therefore has her revenge but perishes herself in the process.

Now that you know the basic outline of the Nibelungenlied, be sure to return for the three articles in which I will examine the themes of Doom, Slaughter, and Heroism, tracing these pre-Christian notions from their flourishing in the Middle Ages to the modern fiction of J.R.R. Tolkien. I hope you will find this subject as fascinating as I do.

You can read more of Amy’s writing on her personal Substack page, Sub-Creations.